What can one say about classically perceived easel painting today, at the start of centuries? Is there anything that would not reek of the banal and not threaten a tautological grinding of words, juggling of notions, critical views, and more or less weighty arguments. And finally, what is there in that inconspicuous, usually closed surface of canvas that so strongly attracts us?

The answer is simple. It’s the difference or, if you prefer, dissimilarity. Each and every work, regardless of time and artist, will carry in it an imprint of individuality, inaccessibility, or for a change of full clarity. It will always, however, remain a difficult equation between the painter and audience, one that has to be resolved.

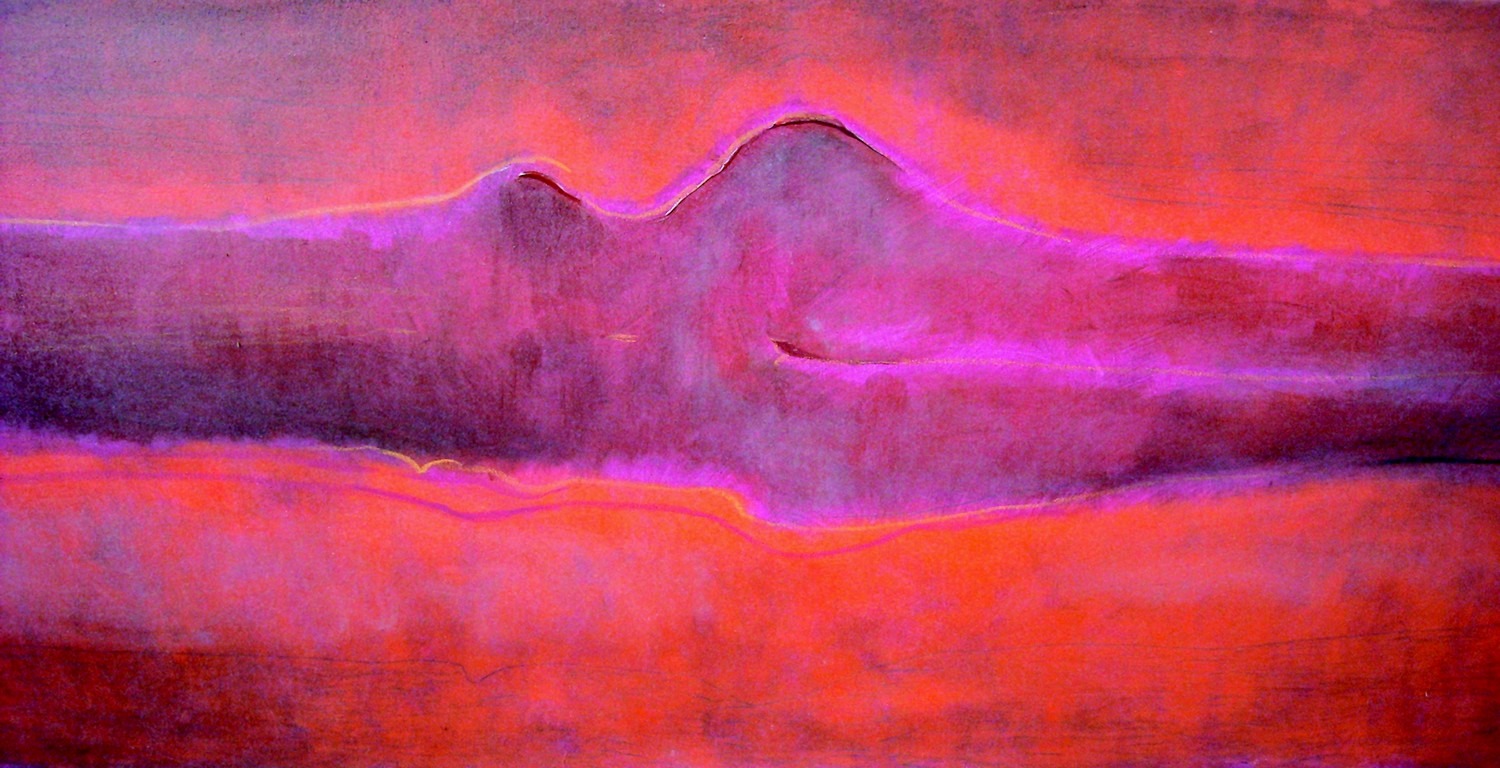

You might ask, why should anyone painstakingly, manually apply layer after layer of colors and harmonized shades, when it is much simpler today to create similar compositions through different “electronic” media? Here lies the primal source of misunderstanding. Because a painting will always be a unique manifestation of human creativity, derived from both spirit and matter. And this is the case of Malina Wieczorek’s paintings, which we are looking at today, where emotions seem to burst

through the canvas.

The figures of the women she portrays are reflected as if in venetian mirrors, unaware of the observations to which they were exposed and in a way sentenced to. Usually they emerge from the inside of the painting, as if shameful, with but a slight gesture or in profile. Ostensibly unified, enchanted in cocoon forms, they defend their individuality. Similar yet different. Alone, yet vividly present among us.

The artist calls them nudes, and this definition can be ascribed both to the body and spirit. Their apparent monochromy, which may irritate the less sophisticated audience, absorbs our attention.Following successive displays of this quiet spectacle, we become more ordered, silent, and friendly towards others.

Jacek Werbanowski, Warsaw